Last week the American Medical Association made headlines when it called gun violence a “public health crisis” and pledged to actively lobby Congress to overturn a 20-year ban on funding for the Center for Disease Control’s research on the issue. It took the horror of 49 people being murdered in Orlando and another 53 suffering injury for the mainstream doctor’s group to finally take a stand on an issue that receives broad support from the scientific community, criminal justice experts and many elected officials. Four years ago, after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, President Obama also called for reversing the CDC research ban; he included $10 million in funding for the agency’s gun violence research in every federal budget since then. Republicans in Congress continue to block it.

This is maddening. Why, in a nation where some 13,431 people died from gun violence and more than 21,000 individuals used guns to commit suicide in 2014 does anyone think a research ban makes sense? The U.S., armed to the teeth with an estimated one firearm for nearly 90% of its 321 million citizens, has the most firearms per capita in the world and accounts for 82% of all gun deaths among 22 nations that include the U.K., France, Australia and Germany. What combination of twisted logic and paranoia has prevented us from pursuing research on the underlying factors associated with gun violence and from developing strategies for reducing the high rate of firearm-related deaths and injuries?

That responsibility rests on the minority of die-hard Second Amendment supporters who have consistently used their outsize influence to drive a pro-gun agenda. Convinced that actual scientific research will bolster the case for tighter gun control measures they prefer to rely on tired rhetoric and false associations to support their arguments. After every shooting, be it massively horrific like in Orlando or the more “ordinary” murder of a wife by an abusive husband, gun control opponents tell us “guns don’t kill people, bad people kill people” or some similar sentiment. When a child finds a loaded gun in a night table and accidentally shoots himself or injures a playmate those same gun rights advocates call it a tragedy; when a middle-aged white man commits suicide by gun it’s a problem with our mental health system.

Meanwhile, the NRA and its members lobbied successfully for gag orders that prevent doctors—even pediatricians—from asking whether patients or their family members keep guns in their homes. They rail against more stringent background checks and laws designed to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers, terrorists or those who are mentally unstable. Keith Ablow, a physician who is part of Fox News’ medical team, said of the AMA’s announcement, “This is just a liberal progressive agenda. They’re going to eat away at gun rights with medical research. That’s not being doctorly, that’s being political. So stop it.” Read more…

In 2008, mental health advocates hailed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act as “historic;” putting an end to what Sen. Edward Kennedy called “the senseless discrimination in health insurance coverage that plagues persons living with mental illness.” The law requires most group health plans to offer coverage for mental health and substance use disorders equal to that provided for medical problems. Two years later, the Affordable Care Act extended this mandate by designating mental health and addiction treatment as one of 10 “essential benefits,” and requiring that Medicaid, as well as private individual and small group plans also provide equal benefits for behavioral health and medical services.

Mental health problems are the leading cause of disability in the US and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than a quarter of adults report having a mental illness at any given time. About half of us will experience mental illness during our lifetime. The intent of the parity legislation is clear; to improve access to desperately needed mental health and addiction services for millions of underserved Americans. Health plans are barred from creating higher deductibles or charging larger co-payments for mental health and addiction disorders treatment. Enrollees no longer have annual and lifetime caps on coverage or face highly restrictive limits on inpatient stays and outpatient visits to behavioral health providers. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that through Medicaid expansion alone, some 32 million individuals could gain access to behavioral health coverage for the first time by 2020.

It all sounds great on paper. But in practice, we are not even close to achieving true parity. Last year, more than half of all people with mental illness still did not receive the treatment they need. And although some 16.4 million more Americans have been able to obtain insurance coverage—and therefore mental health benefits—under the ACA, significant disparities in mental health treatment rates continue to persist between whites and racial and ethnic minorities. As the authors of a new report in Health Affairs put it, “gains in insurance coverage alone are not likely to push forward meaningful reductions in mental health treatment disparities or increase consistently low overall substance use treatment rates.” Read more…

I was out with friends the other night when the conversation turned to the ever-scintillating topic of health insurance. A Swiss woman turned to me and said, “Oh, I hear that Obamacare is really bad now.” A few others guests—mostly self-employed—joined in with woeful tales of rising premiums and deductibles so high in New York’s marketplace plans that they can’t afford to get sick or injured.

Many of these disaffected folks had, like me, signed up in 2015 with Health Republic, a new non-profit consumer operated and oriented plan (CO-OP) that offered reasonable premiums, moderate deductibles and a wide choice of providers. All seemed good with the world. But in late 2015, Health Republic, like many other CO-OPs nationwide, suddenly went belly-up, leaving 209,000 New Yorkers scrambling to find a new insurance plan that offered anywhere near the same choice of doctors and hospitals, low premiums, and a moderate deductible.

A review of the Obamacare landscape indicates that residents of my state are hardly alone in their concern. A recent New York Times survey found that “more than half the plans offered for sale through HealthCare.gov, the federal online marketplace, have a deductible of $3,000 or more.” In Miami, the Times continues, “the median deductible, according to HealthCare.gov, is $5,000. (Half of the plans are above the median, and half below it.) In Jackson, Miss., the comparable figure is $5,500. In Chicago, the median deductible is $3,400. In Phoenix, it is $4,000; in Houston and Des Moines, $3,000.”

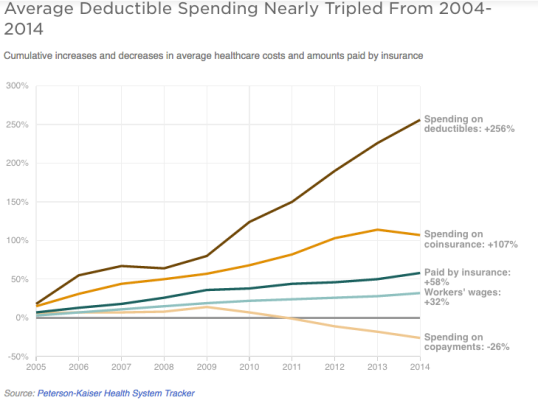

A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Peterson Center on Healthcare found that health insurance deductibles overall rose about eight times faster than wages over the past 10 years. In an NPR piece looking at how rising healthcare costs “weigh on voters” an Oklahoma woman recounts how her family’s only option was to buy an insurance plan on the state exchange with a deductible of $3,000 per family member. Trudy Lieberman, writing at the Center for Health Journalism, recently highlighted another vexing—and costly—problem with the ACA marketplace; “as many as four million people caught in what has become known as the ‘family glitch.’” This “glitch” affects the spouse and children of a family breadwinner who is covered by an employer-provided individual plan costing less than 9.5% of his or her income. Under the ACA, even though the employer does not cover the rest of the family, they cannot receive premium subsidies if they buy coverage on the state or federal marketplace.

Women’s reproductive rights are under attack as never before. Laws are being passed in state after state that result in abortion clinics being shuttered, doctors being forced to stop practicing, millions of women losing access to necessary health care services and, in an ironic twist, an increase in late-term abortion. Add to that the relentless push to “defund” and tar Planned Parenthood, an organization that has been providing vital care to women worldwide for nearly 100 years, and it feels like an all-out assault.

The lattice work of state abortion laws compels women to view sonograms of their fetuses, institutes waiting periods, forces doctors to deliver court-ordered scripts, and most recently, requires abortion clinics to conform to ambulatory surgical center (ASC) standards and their doctors to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. The rationale changes with the type of regulation—informed consent, rights of the unborn, rights of parents and spouses, protecting women from psychological trauma and medical harm—but the underlying goal is always to limit access to abortion.

Over the past decade, abortion foes have focused their efforts most intently on pushing so-called TRAP legislation—Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers—through state legislatures. These are rules that dictate the size of procedure rooms, corridor widths and how far a clinic can be from a hospital. In 17 states these rules apply even to clinics where only medical abortions are performed—a procedure that involves a woman swallowing two pills before returning home. In 14 states abortion providers must have an affiliation with a local hospital; and in 5 states (Texas, Tennessee, Utah, Missouri and North Dakota) they must have admitting privileges.

Last week the battle over clinic regulations finally moved to the Supreme Court. The eight remaining Justices heard arguments in a case involving Texas law HB2 that requires all abortions be performed in licensed ambulatory surgical centers (ASC) and that all doctors practicing at these clinics have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. What is the impact of HB2? In November 2013 when the bill passed the Texas legislature some 14 clinics immediately went out of business as the admitting privileges requirement took effect. Over a dozen other facilities closed during a two-week period in which the ambulatory surgical center requirement was in effect. They reopened only after the Supreme Court issued a stay on that provision and currently Texas has only 10 abortion clinics (out of 36 prior to the law taking effect.).

The Texas clinics closed for two reasons: 1) hospitals routinely refuse to grant admitting privileges to doctors performing abortions, and 2) the cost of upgrading clinics to meet ASC standards is prohibitive, to the tune of $1.6-$2.3 million on “expanding hallway widths and ceiling heights; reconfiguring bathrooms; adding locker rooms, janitorial closets, and parking spaces; upgrading HVAC systems; and recoating floors, walls, and ceilings in special finishes,” according to the Center for Reproductive Rights. Building a new clinic to meet these standards would cost at least $3.5 million.

The Supreme Court must decide if the Texas law violates the Constitution by placing an “undue burden” on women seeking abortion. Defenders of the bill, represented by Texas Solicitor General Scott Keller cite the law’s commitment to ensuring women’s health and safety. But Stephanie Toti, senior counsel at the Center for Reproductive Rights who is representing a coalition of Texas abortion providers in the case and U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli make a forceful and evidence-laden argument that health concerns are unwarranted.

According to evidence presented in the arguments, abortion services have a 99% safety record, with less than 1% of patients experiencing any complications and even fewer requiring further treatment at a hospital. Meanwhile, common procedures that include liposuction, colonoscopy, skin cancer excision, vasectomy, D&C after a miscarriage and even childbirth are allowed to take place in facilities that do not meet the requirements of an ambulatory surgical center. Each of these procedures has a rate of complication equal to or higher than abortion. Justice Elena Kagan pointed out in the questioning phase that liposuction, for example, is nearly 30 times more dangerous than abortion. Read more…

Activism over prescription drug pricing has reached a fever pitch. The recent House subcommittee hearings featuring testimony (or non-testimony in the case of bad-boy Martin Shkreli) from Turing Pharmaceuticals and Valeant executives provided an outlet for public outrage over those companies’ price gouging on life-saving drugs. Meanwhile, presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have both talked up plans to rein in spending on prescription drugs, and even Donald Trump announced that as president he would allow Medicare and Medicaid to bargain with drug companies.

The sordid tale of Shkreli and his company’s 5,000% price increase for a 60-year-old off-patent drug used mainly to treat toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients has been well-documented. Valeant is the other poster child for blatant greed in the pharmaceutical industry with CEO Howard Schiller testifying to the House committee that price increases (most notably for cardiac drugs Isuprel and Nitropress by 536.7% and 236.6%, respectively) accounted for 80% of the company’s growth in 2015. Schiller also told the committee that only 3% of profits were put back into research. Rep. Carolyn Maloney (NY) summed up Valeant’s business strategy as buy a drug, set revenue goals and “then jack up prices.”

The hearing made for good theater but was ultimately disappointing for those of us hoping to actually hear about legislative or other remedies for curbing rising prescription drug costs. Because as Rep. Elijah Cummings pointed out, this problem is “not limited to two companies, it pervades the industry.”

According to Health Affairs, per-capita prescription drug spending in the United States, the highest in the industrialized world, increased by 12.2% in 2014, up from a 2.4% increase in 2013. In a Kaiser Family Foundation health tracking poll , nearly three-quarters of all Americans said the cost of prescription drugs is “unreasonable” and that pharmaceutical companies set the prices too high for their drugs. One-fifth of those who are prescribed medications say they either have to skip doses, cut pills in half, or are unable to afford their prescriptions. Read more…

Earlier this month Medicare fined 2,610 hospitals—a record number—for readmitting too many patients less than 30 days after they were discharged. In 2015, these hospitals will see their Medicare reimbursements cut by as little as .01% to a maximum of 3% in this, the third year that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) has been in place.

The fines “are intended to jolt hospitals to pay attention to what happens to their patients after they leave,” according to Kaiser Health News. The take-home message is that CMS wants hospitals to know that preventing readmission requires more than sending patients home with discharge orders in their hands. Instead, providers need to develop action plans that ensure patients have access to the medications they need, have scheduled follow-up appointments and are connected to community health services that can assist them with managing their health.

The goal of the readmissions reduction program is to improve the quality of care while also cutting Medicare costs associated with patients bouncing back and forth to hospitals. There are already signs of progress. In 2013, 17.5 % of Medicare patients were readmitted within 30 days to hospitals for any condition, down from an average of 19% each of the past five years. That’s good news for CMS, which estimates the cost of 30-day readmissions for Medicare patients to be $26 billion annually with $17 billion of that deemed potentially avoidable if patients had received the right care. Reducing avoidable readmissions by just 10 percent could achieve a savings of $1 billion or more.

Despite this overall trend, progress in reducing readmissions has not been consistent across the board. Safety-net hospitals—mostly public and teaching institutions that serve the largest proportion of low-income patients—are lagging and, according to The Commonwealth Fund, on average, receive higher penalties under the CMS program. They are also far more likely to be penalized: 77 percent of the hospitals with the highest share of low-income patients were penalized for excessive readmissions in the program’s first year vs. just 36 percent of the hospitals with the fewest poor patients. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Congress on policy, has found that lower-income patients have higher readmission rates and major teaching hospitals, which serve large numbers of indigent patients, face the highest penalties. With this in mind, there is growing concern that instead of improving the quality of care, the penalties could worsen health disparities among Medicare beneficiaries who live in low-income areas. Specifically, higher readmission penalties might actually exacerbate the financial challenges safety net hospitals already face, resulting in fewer services, more frequent readmissions, and hospital closures in high-need urban or rural areas.

What can be done? A good first step would be to change the way readmission penalties are calculated. Currently, Medicare tracks the number of patients who go into the hospital for a heart attack, heart failure or pneumonia and then are readmitted within 30 days. This year for the first time Medicare also tracked patients with chronic lung problems and those who underwent elective hip and knee replacements. Hospitals that readmitted patients at a rate higher than expected—keeping in mind the severity of the problem and other confounding factors like gender and age of the patient—saw their reimbursements cut. The question then becomes; are safety-net hospitals providing lower quality care to their disadvantaged patients or are there factors outside the hospital’s walls that are leading to more frequent readmission? Read more…

There’s been a lot of controversy recently about workplace wellness programs: Do they save money for employers on healthcare costs? Can they produce measurable benefits for employee health? Do they unfairly punish people who are unable to participate? Are these programs just a ploy to shift medical costs to unhealthy employees?

Recently Austin Frakt and Aaron Carroll revisited these questions in a piece for the New York Times’ Upshot column, “Do Workplace Wellness Programs Work? Usually Not.” As the title makes clear, Frakt and Carroll come down on the side of the skeptics. I have always appreciated Frakt and Carroll’s analysis of healthcare economics but this time I think they might have missed the mark. A recent analysis of the value of health promotion programs in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (JOEM) has a similar title; “Do Workplace Health Promotion (Wellness) Programs Work?” Instead of answering “Usually Not,” the twenty-plus authors of the JOEM article—all experts in the health promotion field—conclude that some wellness programs work superbly while others are abysmal failures. What separates bad, good and great programs, according to the JOEM authors, is basically “a combination of good design built on behavior change theory, effective implementation using evidence-based practices, and credible measurement and evaluation.” In short, the answer to the question really should be “It Depends…”

Frakt and Carroll came to their conclusion based on a handful of high-profile studies that fail to distinguish the abysmal from the superb. This has been a long-running problem in the health promotion field. The $6 billion corporate health promotion industry is made up of multiple players, including some who promote their vision of “wellness” to executives by promising savings that never materialize. Although half of all companies with 50 or more employees report having health promotion programs, what qualifies as a “program” is poorly defined. A company that offers its employees a financial incentive to fill out a health risk assessment (HRA) questionnaire but offers no other services has a health promotion program. A firm that provides free flu vaccines and access to smoking cessation and Weight Watchers programs is considered to a have health promotion program too. But does anyone really believe that such token efforts will reduce healthcare costs or have any measurable impact on employee health, productivity or even company morale?

For the past year, I have witnessed some of the very good and even “great” programs firsthand. I’ve been working with Ron Goetzel, one of the authors of the JOEM article, and his team at Johns Hopkins University’s Institute for Health and Productivity Studies (IHPS) on a project funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to identify and visit companies with health promotion (or wellness) programs that truly do “work” and have convincing data to prove it. One of the goals of this project is to formulate a series of “best practices” to help guide businesses that want to create high-performing health promotion strategies. Read more…

After more than 40 attempts to pass legislation calling for repeal or significant changes to the health law, opponents of the Affordable Care Act have moved their focus from the House floor to the courthouse. Currently at least four lawsuits are working their way through state and district court—and one case awaits a nod from the Supreme Court—that would make it illegal for the federal government to provide premium subsidies to qualified consumers who buy Obamacare plans in 36 states that failed to set up their own exchanges. Depriving lower-and middle-income Americans of affordable healthcare is bad enough. But these lawsuits are just the latest weapon in the long-term quest to overturn the ACA—and hobble the Obama presidency—by any means necessary.

In fact, it is a strategy grounded in disruptive economics. As Jonathan Gruber, an MIT economist and chief architect of Massachusetts’ health reform law explains it, the Affordable Care Act is designed as a three-legged stool: The first “leg” is new rules that prevent insurers from hiking premiums or denying coverage for people with pre-existing conditions. The second “leg” is the individual mandate that requires all Americans to have health insurance. The third “leg” of the health law is the federal subsidies that make this insurance affordable to lower and middle-income people. Knock out one leg and the whole law becomes economically unfeasible.

Where are the potential weaknesses? The first leg of the stool is solid: There is bipartisan support for ending discriminatory practices in the insurance industry. The second leg is strengthened by the Supreme Court decision that found the individual mandate to be constitutional and enforceable. But the third leg—federal subsidies to help lower-income families and individuals pay for health coverage—is considered wobbly enough by conservatives to collapse with the right legal pressure. Their focus now is on the wording of a section of the Affordable Care Act that authorizes the federal subsidies. The law allows that tax subsidies may be available to qualified citizens who enroll in insurance plans “through an Exchange established by the State.” Read more…

For about 5% of the population, President Obama’s promise “if you like your insurance, you can keep it” was clearly off the mark. They like it and they can’t keep it—or they will have to pay more for it. Their anger and sense of betrayal are being used by opponents of the Affordable Care Act to discredit the President and highlight the law’s alleged shortcomings. But let’s be honest; how great was that insurance in the first place? Sure it might have been cheap, but many policyholders were one illness or accident away from crushing bills and even bankruptcy. And is it worth it to allow insurers to keep selling these policies to cherry-picked healthy people, even if it threatens to raise premiums for many of the 40 million uninsured people who have been priced out of the individual market because of their health status, age or gender?

The answer, for at least another year, is “yes.” Under pressure from anxious Democrats in Congress—including some like Sen. Mary Landrieu (LA) who are facing tough reelection battles—Obama today proposed an administrative fix to the ACA that would let insurance companies renew plans through 2014 that do not meet the benefit standards of the health care law. State insurance commissioners and insurance companies will now make the final decision on whether they will renew cancelled policies on the individual market. Insurers would have to notify plan subscribers of alternative plans they could purchase through the exchanges, as well any benefits they would miss out on by staying with their existing policy. As the President put it: “the Affordable Care Act is not going to be the reason why these companies are canceling your plan.” Read more…

It was a huge relief to Carol Thompson in 2011 when her breast cancer drug Femara (letrozole) went off patent and became available in a generic version. With a high deductible in her private insurance plan, Thompson was forking over $450 for a month’s supply of the life-saving drug. After the generic hit the market she was thrilled to find letrozole available for just $11 a month at Costco. But curious to find out if she could save even more at another pharmacy, Thompson made a few calls to local chains and mail-order services to compare prices.

What she found was astonishing: prices for letrozole ranged wildly, from $450 for a month’s supply at CVS to just $14 at a local, independent drug store. Pity the person who assumes that big national chains like CVS and Target that buy generics wholesale in large quantities will naturally provide the best value.

Thompson’s story is told in a recent PBS NewsHour segment that takes a wider look at the wildly different prices pharmacies charge for medications that include some of the most common prescriptions drugs.

What 66-year-old Carol Thompson encountered in Edina, Minnesota should be an eye-opener for any of us who assume the price we pay for generic drugs is more or less the same from pharmacy to pharmacy. The explanations from chains like CVS for why some of their generic drugs cost so much is that the price reflects the added cost of having 24 hour prescriptions services, drive-through pharmacies and so many local brick and mortar stores. But this explanation rings false: For prescription drug buyers it is just the latest case of haggling for health care. Read more…